It is a longer than expected ascent via an earthy, unprotected, zigzag road to the top of the mountain. I’m happily (nervously) in the backseat. Our driver — a real pro and a local — handles the road almost flawlessly. The slope, the gravel surface, the pinching spaces are all on my mind as our car continues, but no sweat for the man behind the wheel. Combined with a dozen or so 360-degree inclining turns as the path upward leads to safe harbor right outside of our host’s home. For me, it’s one of the most nerve-wracking rides I ever experience, for the locals, it’s a typical part of most days.

It’s not my first ever visit to Goukou (沟口), one of the towns of Maoxian (茂县). I was here once before, about 6 months earlier, specifically to photograph the town. But I never went up any of the town’s mountains. Down at ground level, there are growing and thriving communities. And the river is a big component and presence. Up here, one of the first things I notice is that the sun is rather strong. It doesn’t take long before I have sunburn on my face. And the infrastructure is the reverse of what one might observe in the town area, where construction and development are underway — here, communities are in the long process of eroding away.

Of course, it’s been the case for a long time that the people of the mountains are spread out, and seemingly few. And there are still people up here living proper, unhindered lives. Well, kind of. While the handful of still-standing homesteads enjoy a good deal of space and resources and privacy, the few accounts I have with their occupants all claim to only live in the mountains for only a portion of the year. The rest of the year is at another home, at one of the larger, connected, modern towns nearby.

All things considered, I have deep respect for those that live high in the mountains. It’s remote, dangerous, physically demanding, and potentially quite costly.

Kudos to the people who built, and maintain, these crazy roads.

The homesteads are an exemplary display of practical and fundamental living. Tools and resources are used to their limits, stored long term, while what looks like junk is kept around in case. Livestock and crops provide the bulk of the sustenance but also are harvested for commercial purposes. Preservation is a vital concept. Large volumes of land provide flexibility to do this. Still, land is primarily dedicated to harvesting. There are terraces and plots in just about every direction and any size. When there is only space for a tiny garden, there will probably be one.

We meet up with a former resident of the mountain. Our first time meeting was actually in Chengdu. He no longer lives in Goukou, or even Maoxian. But he knows his way around the mountain, and he knows the people still living on the mountain, and he knows where his home used to stand. I can see on him, hints of fondness for this mountain, even though his overall standard of living, economic status are unquestionably improved since moving away.

As a small child growing up on the mountain he spoke another language natively, the language of the Qiang (羌话), which has dialects of its own, depending on the mountain range. It has no formal written language. He learned Mandarin (普通话), or I guess “Sichuanese” (四川话), primarily from school and life away from the mountain.

He is gracious in pointing out many things for us. The land on the mountain has changed. There was a time when the mountain was mostly covered in forest -> over time, much of the forest was cleared away as residents and their families expanded -> at some point, the government pushed a reclamation effort of sorts (for environmental purposes I suppose, maybe a save-the-pandas thing) and started replanting trees and vegetation -> some of the reclamation efforts were abandoned or resisted, so there is not a clear direction as of today. Nonetheless, the government offers a relocation payment to families with homes here. Our friend says he and his family gave up their home here and were compensated with something like 200,000 RMB. I don’t remember the exact number or any “terms” of the deal. Other families got similar offers, but obviously, some continue to hold out.

We take a look at what was once his home, it is now a foundation-shaped plot used for plants and crops by other relatives still living here. Resourceful, yet poignant.

Either way, Mother Nature never takes breaks — the lands modified for habitability and cultivation do not always last. Some of the man-modified segments of land have slowly collapsed into streams of rubble. Paths from one homestead to a neighbor might require another route than from ten years ago. The shape of the mountain sometimes retaliates. Our friend points out how some familiar spots around the mountain from his youth are now completely gone or changed, notably with a much steeper slope now.

I guess there is some potential to continuing to own and operate a homestead out here, as fewer people choose to stay there is more space to work with — if one puts in the considerable effort and times things correctly. It’s a lot to manage and maintain, exacerbated by the remoteness. Whatever the case is, folks migrate to the towns and the cities. To stick around here takes a great deal of cooperation, dedication, and ingenuity. And probably also a good bit of stubbornness.

Most homesteads have their fair share of chickens and goats. Sometimes pigs are also kept.

An old primary school, no longer in use, is close by. Our friend attended the school, and he points out the building to us. While it’s been shut down, it looks no bigger than a house. Even when it was at its most active, I would guess fewer than a dozen children were ever in attendance at a single time. Nowadays, children will go to one of the larger towns to attend school and are likely to board there.

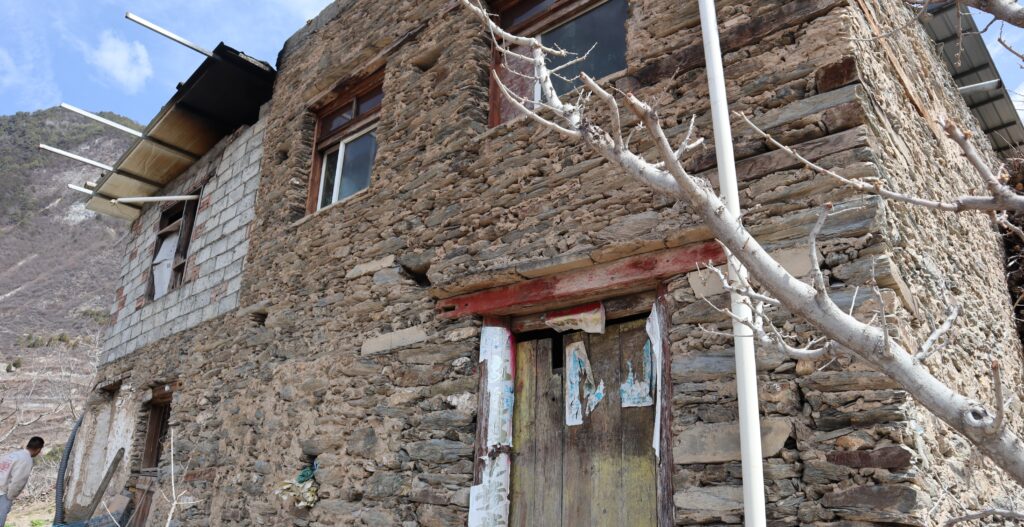

Though I cannot offer any actual architectural analysis, I do wish to observe how the ruins of some homes here are of similar style to the prototypical Qiang sort. The sort found in the more recognized Qiang cultural hotspots. It’s of interest to me because in those areas, there is rather intentional emphasis on flaunting the local Qiang style, which is typically demonstrated with stone-built homes. But here there is no such directive. Just things built to last with the knowledge and resources available. Over time, the structures that are still functioning are a patchwork of different materials and styles.

I too develop a fondness for the mountain, the homestead, and the people here too. But I also am thankful I have the option to visit, while living in a town with modern infrastructure and amenities and conveniences. A lot of things that are missing here. Yet I am moved in a unique, essential way — to get to learn, explore, taste life up here. And no way does any town or city beat the views.

Leave a Reply